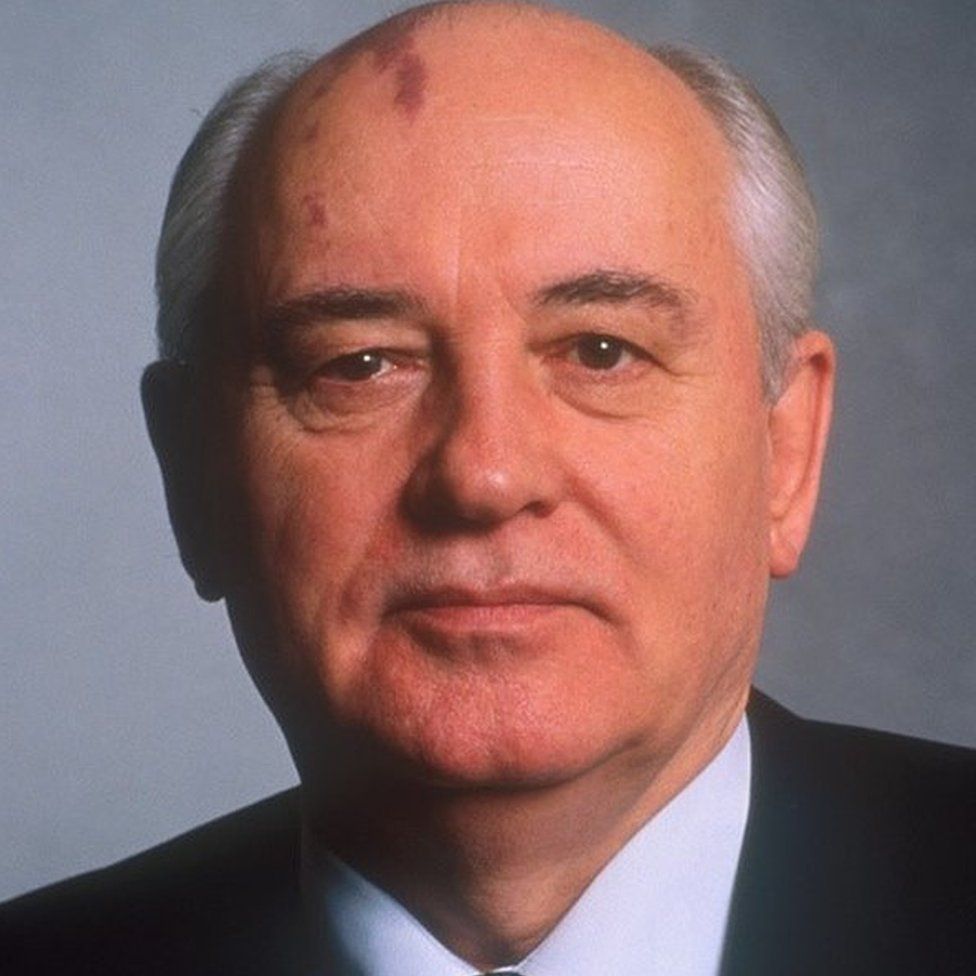

Mikhail Gorbachev was one of the most influential political figures of the 20th Century.

He presided over the dissolution of a Soviet Union that had existed for nearly 70 years and had dominated huge swathes of Asia and Eastern Europe.

Yet, when he set out his programme of reforms in 1985, his sole intention had been to revive his country’s stagnant economy and overhaul its political processes.

His efforts became the catalyst for a series of events that brought an end to communist rule, not just within the USSR, but also across its former satellite states.

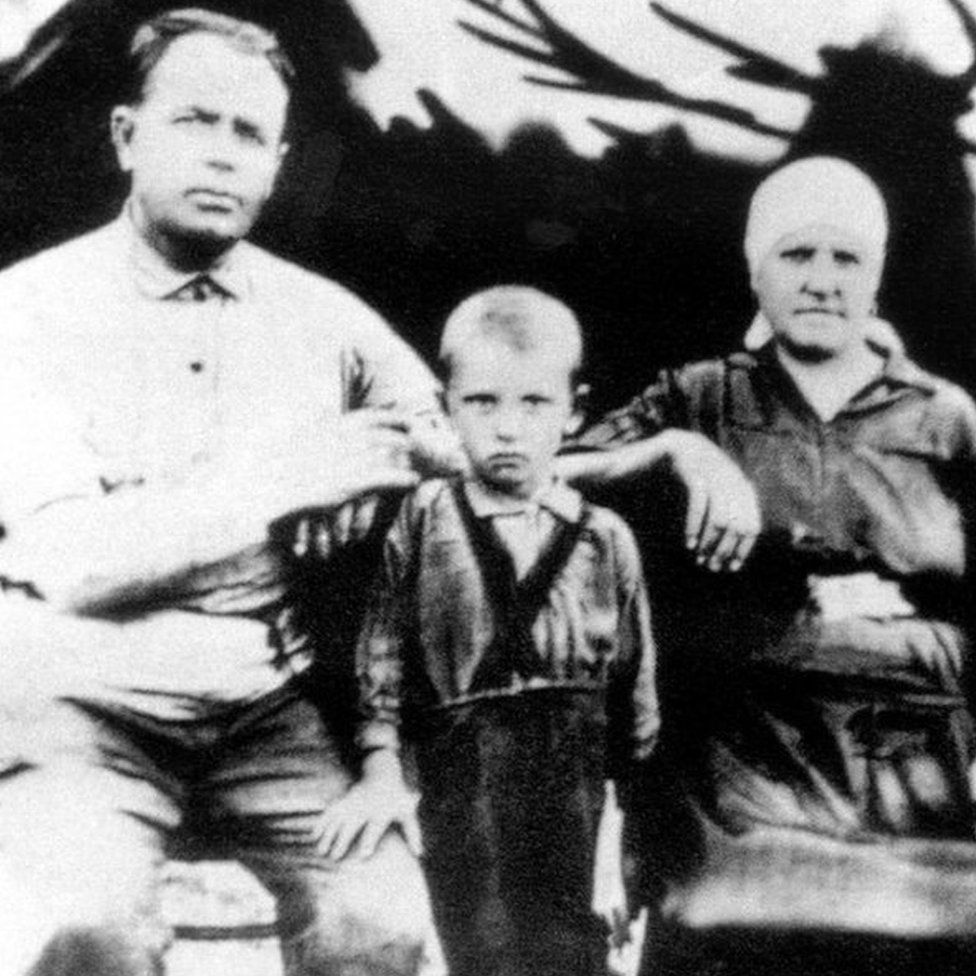

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev was born on 2 March 1931 in the Stavropol region of southern Russia.

His parents both worked on collective farms and the young Gorbachev operated combine harvesters while in his teens.

By the time he graduated from Moscow State University in 1955 he was an active member of the Communist Party.

On his return to Stavropol with his new wife Raisa, he began a rapid rise through the regional party structure.

Gorbachev was one of a new generation of party activists who became increasingly impatient with the ageing figures at the top of the Soviet hierarchy.

By 1961 he was regional secretary of the Young Communist League and had become a delegate to the Party Congress.

His role as an agricultural administrator gave him the opportunity to introduce innovations and this, coupled with his status in the party, gave him considerable influence in the region.

In 1978 he went to Moscow as a member of the Central Committee’s Secretariat for Agriculture and just two years later he was appointed a full member of the Politburo.

During Yuri Andropov’s tenure as general secretary, Gorbachev made a number of trips abroad, including a 1984 visit to London where he made an impression on Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

In a BBC interview she said she was optimistic about future relations with the USSR. “I like Mr Gorbachev,” she said. “We can do business together.”

Gorbachev had been expected to succeed Andropov when the latter died in 1984 but instead the ailing Konstantin Chernenko became general secretary.

Within a year, he too was dead and Gorbachev, the youngest member of the Politburo, succeeded him.

He was the first general secretary to have been born after the 1917 revolution and was seen as a breath of fresh air after the stagnation of the Leonid Brezhnev years.

Gorbachev’s stylish dress and open, direct manner were unlike those of any of his predecessors, and Raisa was more like an American first lady than a general secretary’s wife.

His first task was to revive the moribund Soviet economy, which was almost at the point of collapse.

He was also shrewd enough to understand that there needed to be root-and-branch reform of the Communist Party itself if his economic reforms were to succeed.

Gorbachev’s solution brought two Russian words into common usage. He said the country needed “perestroika” or restructuring and his tool for dealing with it was “glasnost” – openness.

“You’re lagging behind the rest of the economy,” he told the communist bosses of Leningrad, which was renamed Saint Petersburg in 1991. “Your shoddy goods are a disgrace.”

But it was not his intention to replace state control with a free market economy – as he made clear in a speech to party delegates in 1985.

“Some of you look at the market as a lifesaver for your economies. But, comrades, you should not think about lifesavers but about the ship, and the ship is socialism.”

His other weapon for dealing with the stagnation of the system was democracy. For the first time there were free elections for the Congress of People’s Deputies.

This relaxation of the repressive regime caused a stirring among the many diverse nationalities that comprised the sprawling Soviet Union. Riots in Kazakhstan in December 1986 heralded a period of unrest.

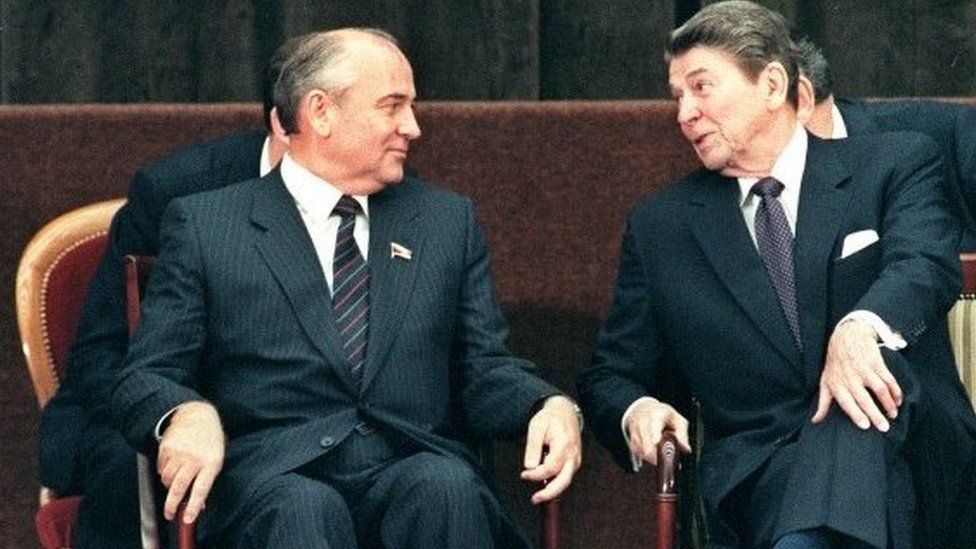

Gorbachev wanted to end the Cold War, successfully negotiating with US President Ronald Reagan for the abolition of a whole class of weapons through the Intermediate Nuclear Forces treaty.

And he announced unilateral cuts in Soviet conventional forces, while finally ending the humiliating and bloody occupation of Afghanistan.

But his toughest test came from those countries that had been unwillingly annexed by the Soviet Union.

Here openness and democracy led to calls for independence, which initially Gorbachev put down by force.

The break-up of the USSR began in the Baltic republics in the north. Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia broke free from Moscow, starting a rollercoaster that spread to Russia’s Warsaw Pact allies.

It culminated on 9 November 1989 when, following mass demonstrations, the citizens of East Germany, the most hard-line of the Soviet satellites, were allowed to cross freely into West Berlin.

Gorbachev’s reaction was not to send in tanks, the traditional Soviet reaction to such blatant opposition, but to announce that reunification of Germany was an internal German affair.

In 1990, Gorbachev was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize “for the leading role he played in the radical changes in East-West relations”.

But by August 1991 the communist old guard in Moscow had had enough. They staged a military coup and Gorbachev was arrested while holidaying on the Black Sea.

The Moscow party boss, Boris Yeltsin, seized his chance, ending the coup, arresting the demonstrators and stripping Gorbachev of almost all his political power in return for his freedom.

Six months later, Gorbachev had gone; the Communist Party itself was outlawed and Russia set out on a new, uncertain, future.

Mikhail Gorbachev continued to play a vocal role in both Russian and international matters, but his reputation abroad was always higher than at home.

When he stood for the Russian presidency in 1996 he received less than 5% of the vote.

During the 1990s he took to the international lecture circuit and kept up contacts with world leaders, remaining a heroic figure to many non-Russians, winning numerous awards and honours.

He suffered a personal blow in 1999 when Raisa died of leukaemia. Her constant presence at his side had lent a humanising touch to his political reforms.

Gorbachev remained a strong critic of President Vladimir Putin, who he accused of running an increasingly repressive regime.

“Politics is increasingly turning into imitation democracy, said Gorbachev, “with all power in the hands of the executive branch.”

However, in 2014, Gorbachev defended the referendum that led to Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

“While Crimea had previously been joined to Ukraine based on the Soviet laws, which means party laws, without asking the people,” Gorbachev declared, “now the people themselves have decided to correct that mistake.”

On Gorbachev’s 90th birthday in March 2021, President Putin praised him as “one of the most outstanding statesmen of modern times who made a considerable impact on the history of our nation and the world”.

And Gorbachev’s own views of his legacy? It was right to end the totalitarian system and the Cold War, and reduce nuclear weapons, he said.

But there was still lament over the coup and the end of the Soviet Union. Many Russians still hold him responsible for its collapse.

Although a pragmatic and rational politician, Mikhail Gorbachev failed to realise that it was impossible to bring in his reforms without destroying a centralised communist system that millions in the USSR and beyond no longer wanted.